Can Nvidia fend off the barbarians at the gate? A company deep dive

The rise of Nvidia is fascinating, having been founded in 1993 with a plan to create 3D graphics cards for gaming and multimedia markets. In 1999, Nvidia announced the GPU, the graphics processing unit, which began the era of reshaping the computing industry.

Very early on, Nvidia saw—perhaps inspired by Steve Jobs’ “full integration” thinking—that the creation of a product ecosystem not only adds value for clients, but increases their switching costs. This led to the development and launch of the CUDA Toolkit in 2006, which opens the parallel processing capabilities of GPUs, leading to the breakthrough AlexNet neural network in 2012. In 2018, Nvidia reinvented computer graphics with the RTX platform—the first GPU capable of real-time ray tracing (a method of graphics rendering that simulates the physical behaviour of light).

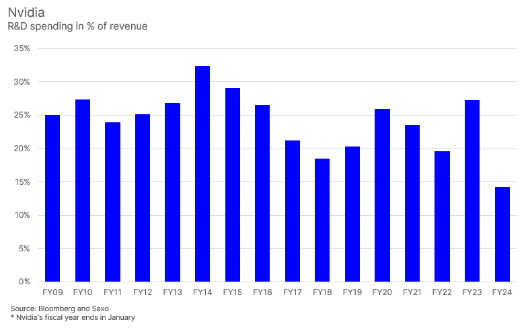

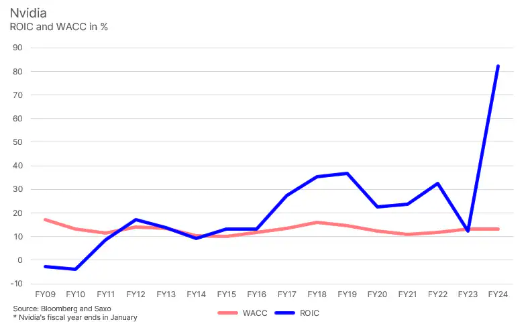

A high-quality company creates over time deep moats that are difficult for competitors to overcome, and Nvidia’s intensive research and development (R&D) spending over the years has laid the groundwork for its innovation record. Nvidia spent an average of more than 25% on R&D annually in the years leading up to fiscal year 2017. That represents an R&D intensity far above Nvidia’s competitors, and multiples above the average company. It was this high R&D spending that distorted Nvidia’s return on invested capital (ROIC) figures for years on end, giving the company the appearance of lower quality. This is an important lesson for investors—high revenue growth and high R&D spending in percentage of revenue are two important markers of future success.

Incredible development in fundamentals

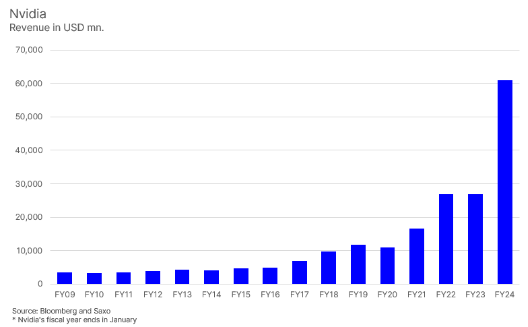

Nvidia saw the future earlier than anyone else, and was well positioned to take advantage of the major shifts in the computing industry towards parallelisation and advancements in machine learning. When you look at Nvidia’s historical revenue trend, it becomes clear that the fiscal year 2017 (ending January 2017) is the moment when things changed. Up until this point, Nvidia made the majority of its profits from selling GPUs used for gaming.

But in 2016, two trends began to emerge. Bitcoin exploded higher, generating large profits for Bitcoin miners in need of more and more GPUs to crunch the numbers to unlock the cryptocurrency’s validation process. Simultaneously, the machine learning community saw major advancements, built on Nvidia’s GPUs.

In late 2022, OpenAI launched ChatGPT, which can be seen as Nvidia’s company-defining moment. For the first time, there was a useful consumer interface with a large language model (LLM) that could process questions and return useful answers to a wide range of domains. The technology sector immediately saw the potential of this AI technology and invested accordingly, lifting Nvidia’s revenue to USD 60.8bn in FY24, up from USD 27bn the year before. In 15 years, Nvidia has lifted its revenue from USD 3.4bn to USD 60.9bn, and is projected to deliver FY25 revenue of USD 113.8bn and USD 143.2bn in FY26.

When we talk about a quality company, the ultimate yardstick is ROIC. After FY16, Nvidia’s decades of intense R&D spending began to pay off, with ROIC jumping from just above 10% to the 30-40% range. In its latest fiscal year, the ROIC rose to a staggering 82%—far eclipsing Nvidia’s cost of capital. This is the main explanation for Nvidia’s strong share price performance—high ROIC paired with low need for capital expenditures (CAPEX).

The ‘secret sauce’

Nvidia's low CAPEX needs is a key ingredient to its success, as it reduces the amount of capital the company needs to reinvest in the business. Nvidia designs and develops the intellectual property for its advanced AI chips, but gets TSMC to manufacture its GPUs, effectively meaning it has outsourced the capital-intensive part of the business.

Another ingredient is the software that Nvidia has developed over the years to speed up R&D for applications using its GPUs, with the CUDA Toolkit platform as crown jewel. This is the deepest point of Nvidia’s economic moat.

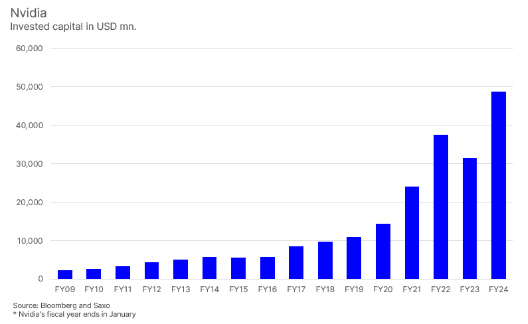

A high ROIC is key for generating strong shareholder returns, but this is not exclusive to companies in high-growth industries. In the case of Nvidia, revenue is also rapidly growing, reflected in its invested capital (i.e., all the capital Nvidia is deploying to run its business). Nvidia’s invested capital approached close to USD 50bn in the recent fiscal year. This is ultimately the engine for high shareholder returns—an expansion of ROIC combined with high or increasing growth rates.

The ultimate indicator of Nvidia’s success has been its share price performance. Nvidia’s total return has been 35.6% annualised since December 2003, compared to 7.9% for the MSCI World over the same period. The semiconductor industry group has delivered 13% annualised in the same period. The main question for investors is whether Nvidia will turn out to be an enduring company that can fend off competition for years and become as powerful as Apple and Microsoft. Time will tell, and the only thing we know from history is that no company remains at the top forever. Competition and change eventually disrupt everyone.

The barbarians at the gate

Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon, is quoted as saying that “your margin is my opportunity”. In retailing, it could mean cutting out one layer in the distribution network. But in technology, it could also mean that if a critical supplier earns a fat margin, there is a lot of money to be saved for finding a cheaper alternative. This is exactly what might be brewing in the GPU industry.

It is no secret that many US technology companies are pursuing their own purpose-built AI chips, just as Apple developed the M1 chip. If you can develop the design and intellectual property for the AI chip, you can get TSMC to manufacture it in its foundries.

But, as described, the AI industry is not only about hardware. It’s also about software. Nvidia’s CUDA Toolkit is a development environment for creating high-performance GPU-accelerated applications. Even if you find an alternative AI chip, you need specialised software for making applications.

And competition in the AI development environment is coming for Nvidia’s lunch as Meta, Microsoft, and Google collaborate on the development of Triton, which will be able to run on a range of AI chips. Whether these US tech giants can build a good enough alternative remains to be seen—Nvidia has invested billions over the years into its integrated software. So while competition is certainly coming for Nvidia, it might be that Nvidia’s moat is too deep to overcome and the company is simply the next new natural “monopoly”.

Existing or potential new investors in Nvidia should consider the three most obvious risk factors related to the company:

- Supply chain disruptions: GPU manufacturing sits on a complex global supply chain. Any major disruption, whether due to geopolitical tensions (such as trade wars or sanctions) or natural disasters, can lead to shortages of critical components, delayed production, and increased costs.

- Market competition and technological change: The semiconductor and GPU markets are highly competitive, with major players like AMD, Intel, and new entrants continually striving to innovate. Failure to keep up with technological advancements or anticipate market trends could result in losing market share. Additionally, disruptive technologies could render Nvidia's current products less relevant.

- Regulatory and legal challenges: GPUs have become a crucial part of the technology “arms race” between the US and China. This could lead to export controls by the US government, which would limit Nvidia’s revenue outlook in China. Nvidia could also face US antitrust regulation if regulators find its ecosystem prevents innovation and competition.